A Crash Course in Python: Part 3

Contents

A Crash Course in Python: Part 3#

Lambda Functions#

Syntax

lambda arguments : expression

An anonymous function means that a function is without a name

The lambda keyword is used to create anonymous functions

Python lambda properties:#

can have any number of arguments but only one expression, which is evaluated and returned.

used when objects are required

syntactically restricted to a single expression

have various uses in particular fields of programming, besides other types of expressions in functions.

Example: Lambda Function#

calc = lambda num: "Even number" if num % 2 == 0 else "Odd number"

print(calc(20))

Even number

Example 2: Lambda Function#

string = "Drexel Dragons"

# lambda returns a function object

print(lambda string: string)

<function <lambda> at 0x0000020320AA00D0>

Explanation: The lambda is not being called by the print function, but returning the function object and the memory location. So, to make the print to print the string first, we need to call the lambda so that the string will get pass the print.

Example 2: Invoking lambda return value to perform various operations#

# Returns all of the non-digit parts of a string

filter_nums = lambda s: "".join([ch for ch in s if not ch.isdigit()])

print("filter_nums():", filter_nums("Drexel101"))

filter_nums(): Drexel

# Adds an exclamation point at the end of a string

do_exclaim = lambda s: s + "!"

print("do_exclaim():", do_exclaim("I am tired"))

do_exclaim(): I am tired!

In-Class Exercise:#

Use the Lambda function to find the sum of all integers in a string

Input an integer n

Use a for loop to extract the individual integers

Print the sum

# Type your solution here

# # finds the sum of all integers in a string

find_sum = lambda n: sum([int(x) for x in str(n)])

print("find_sum():", find_sum(104))

find_sum(): 5

Example: Use of lambda function inside a function#

l = ["1", "2", "9", "0", "-1", "-2"]

# sort list[str] numerically using sorted() a build in function

# and custom sorting key using lambda

print("Sorted numerically:", sorted(l, key=lambda x: int(x)))

Sorted numerically: ['-2', '-1', '0', '1', '2', '9']

# filter positive even numbers

# using filter() and lambda function

print(

"Filtered positive even numbers:",

list(filter(lambda x: not (int(x) % 2 == 0 and int(x) > 0), l)),

)

Filtered positive even numbers: ['1', '9', '0', '-1', '-2']

# added 10 to each item after type and

# casting to int, then convert items to string again

print(

"Operation on each item using lambda and map()",

list(map(lambda x: str(int(x) + 10), l)),

)

Operation on each item using lambda and map() ['11', '12', '19', '10', '9', '8']

Object Oriented Concepts#

Classes#

Is a logical group that contains attributes and methods

This allows programs to be created with simple objects that are easy to read and modify

It says that all instances of a class have the same attributes and methods

Example use case:#

Suppose you have a bunch of rubber ducks in your store and you want to keep an inventory where each duck has some attributes (e.g., color, size, name). This is a perfect use case for a class. You can define a class that is rubber ducks, which has a set of definable attributes.

Classes are created by the keyword

classAttributes are variables that belong to a class

Attributes can be accessed via the (

.) operator (e.g.,class.attribute)

Start with defining the class#

class Rubber_Duck: # Defines the class

pass # passes when called

We created a class that does nothing :)

Objects#

An object is a variable that has a state and behavior associated with it.

An object can be as simple as a integer

An object can be as complex as nested functions

Components of Objects#

State: It is represented by the attributes of an object. It also reflects the properties of an object.

Behavior Methods of the object, and how the object interacts with other objects

Identity The Unique name that is used to identify the object

Let’s build and object from the class#

obj = Rubber_Duck()

This created an object of the type

Rubber_Duck

The self class#

Class methods have an initial parameter which refers to itself

If we call

myobj.method(arg1, arg2)we are actually callingmyobj.method(myobj, arg1, arg2)

To simplify this in classes, the

selfrefers to the object

The __init__ method#

def __init__(self, arg):

self.arg = arg

This method is called when the object is instantiated

In-Class Exercise: Creating a class and objects with attributes and instance attributes#

Task:

Create a Class Rubber_Duck

Add an attribute

obj_typeand set it equal to “toy”Use the

__init__function to set the nameInstantiate two objects

luke_skywalkerwith a nameLuke Skywalkerandleia_Organawith a nameLeia Organa

# Type your solution here

class Rubber_Duck: # Defines the class

# Class attribute

obj_type = "toy"

# Instance attribute

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

# Object instantiation

luke_skywalker = Rubber_Duck("Luke Skywalker")

leia_organa = Rubber_Duck("Leia Organa")

Test#

# Accessing class attributes

print(f"Luke Skywalker is a {luke_skywalker.__class__.obj_type}")

print(f"Leia Organa is a {leia_organa.__class__.obj_type}")

# Accessing instance attributes

print(f"My name is {luke_skywalker.name}")

print(f"My name is {leia_organa.name}")

Luke Skywalker is a toy

Leia Organa is a toy

My name is Luke Skywalker

My name is Leia Organa

Adding a Method#

You can add methods within the class

Task:

Add a method to the class

Rubber_Duckthat completes the linef"My name is {leia_organa.name}"whenclass.speakis called

# Your solution goes here

class Rubber_Duck: # Defines the class

# Class attribute

obj_type = "toy"

# Instance attribute

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def speak(self):

print(f"My name is {self.name}")

# Object instantiation

luke_skywalker = Rubber_Duck("Luke Skywalker")

leia_organa = Rubber_Duck("Leia Organa")

Test#

luke_skywalker.speak()

leia_organa.speak()

My name is Luke Skywalker

My name is Leia Organa

Inheritance#

Inheritance allows one class to inherit properties from another class

Usually referred to as child and parent classes

It allows you to better represent real-world relationships

Code can become much more reusable

It is transitive meaning that if Class B inherits from Class A than subclasses of Class B would also inherit from Class A

Inheritance Example#

Syntax

Class BaseClass: {Body} Class DerivedClass(BaseClass): {Body}

Step 1: Create a parent class with a method#

Create a parent class named

Personthat defines anameandageAdd a Class method that prints the name and title

# Your solution goes here

class Person:

# Constructor

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

# To check if this person is an employee

def Display(self):

print(self.name, self.age)

Testing#

jedi = Person("Darth Vader", 56)

jedi.Display()

Darth Vader 56

Step 2: Creating a Child Class;#

Create a child class of

Person,Jedithat has a methodPrintthat printsJedi's use the force

# Your solution goes here

class Jedi(Person):

def Print(self):

print("Jedi's use the force")

Testing#

# instantiate the parent class

jedi_info = Jedi("Darth Vader", 56)

# calls the parent class

jedi_info.Display()

# calls the child class

jedi_info.Print()

Darth Vader 56

Jedi's use the force

Step 3: Adding Inheritance#

Starting with the base Class

Personadd a method togetNamethat returns thenameAdd a method

isAlliancethat establishes if the person is part of the Rebel Alliance, the default should beFalseAdd a inherited child class

Alliancethat changesisAlliancetoTrue

# Your solution goes here

class Person:

# Constructor

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

# Function that gets the name

def getName(self):

return self.name

# Function that returns if the person is part of the alliance

def isAlliance(self):

return False

# Inherited child class

class Alliance(Person):

# This will change the isAlliance class to True

def isAlliance(self):

return True

Test#

darth_vader = Person("Darth Vader", 56)

print(darth_vader.getName(), darth_vader.isAlliance())

luke_skywalker = Alliance("Luke Skywalker", 21)

print(luke_skywalker.getName(), luke_skywalker.isAlliance())

Darth Vader False

Luke Skywalker True

Exercise: Classes with Methods for Strings#

When you build a class there are a bunch of built-in magic methods methods. These can be used to do simple operations

In this exercise we are going to use the methods __str__ and __repr__

__str__ - To get called by built-int str() method to return a string representation of a type.

__repr__ - To get called by built-int repr() method to return a machine readable representation of a type.

Tasks#

Build a class called

Personthat records the first namefirst_name, last namelast_name, and ageageAdd built in methods that returns a

__str__as an f-string. It should read “{First Name} {Last Name} is {age}”Add built in methods that returns a

__repr__as an f-string. It should read “{First Name} {Last Name} is very old, they are {age}”Try this with a person named “Luke” “Skywalker” age “80”

Since you added the

__str__and__repr__functions the object can act as a string. Try this by printing the object using an f-string.You can print the machine readable version using the following syntax `f”{object!r}

# Type your code here

class Person:

def __init__(self, first_name, last_name, age):

self.first_name = first_name

self.last_name = last_name

self.age = age

def __str__(self):

return f"{self.first_name} {self.last_name} is {self.age}."

def __repr__(self):

return f"{self.first_name} {self.last_name} is very old, they are {self.age}"

new_person = Person("Luke", "Skywalker", "80")

f"{new_person}"

'Luke Skywalker is 80.'

f"{new_person!r}"

'Luke Skywalker is very old, they are 80'

*args and **kwargs#

What is Python *args ?#

The special syntax *args in function definitions in python is used to pass a variable number of arguments to a function. It is used to pass a non-key worded, variable-length argument list.

The syntax is to use the symbol * to take in a variable number of arguments; by convention, it is often used with the word args.

What *args allows you to do is take in more arguments than the number of formal arguments that you previously defined. With *args, any number of extra arguments can be tacked on to your current formal parameters (including zero extra arguments)

For example, we want to make a multiply function that takes any number of arguments and is able to multiply them all together. It can be done using *args.

Using the _, the variable that we associate with the _ becomes an iterable meaning you can do things like iterate over it, run some higher-order functions such as map and filter, etc.

Example: Simple *args Example#

def myFun(*args):

for arg in args:

print(arg)

myFun("Hello", "Welcome", "to", "Drexel")

Hello

Welcome

to

Drexel

Example of *args with First Extra Argument#

def myFun(arg1, *args):

print("First argument :", arg1)

for arg in args:

print("Next argument through *args :", arg)

myFun("Hello", "Welcome", "to", "Drexel")

First argument :

Hello

Next argument through *args : Welcome

Next argument through *args : to

Next argument through *args : Drexel

What is Python **kwargs?#

The special syntax **kwargs in function definitions in python is used to pass a keyworded, variable-length argument list. We use the name kwargs with the double star. The reason is that the double star allows us to pass through keyword arguments (and any number of them).

A keyword argument is where you provide a name to the variable as you pass it into the function.

One can think of the kwargs as being a dictionary that maps each keyword to the value that we pass alongside it. That is why when we iterate over the kwargs there doesn’t seem to be any order in which they were printed out.

Example using **kwargs#

def myFun(**kwargs):

for key, value in kwargs.items():

print(f"{key} {value}")

# Driver code

myFun(first="Welcome", mid="to", last="Drexel")

first Welcome

mid to

last Drexel

Example using *args and **kwargs#

def myFun(arg1, arg2, arg3):

print("arg1:", arg1)

print("arg2:", arg2)

print("arg3:", arg3)

# Now we can use *args or **kwargs to

# pass arguments to this function :

print("Version with *args")

args = ("Welcome", "to", "Drexel")

myFun(*args)

Version with *args

arg1: Welcome

arg2: to

arg3: Drexel

print("Version with **kwargs")

kwargs = {"arg1": "Welcome", "arg2": "to", "arg3": "Drexel"}

myFun(**kwargs)

Version with **kwargs

arg1: Welcome

arg2: to

arg3: Drexel

def myFun(*args, **kwargs):

print("args: ", args)

print("kwargs: ", kwargs)

# Now we can use both *args ,**kwargs

# to pass arguments to this function :

myFun("Welcome", "to", "Drexel", first="Come", mid="to", last="Drexel")

args: ('Welcome', 'to', 'Drexel')

kwargs: {'first': 'Come', 'mid': 'to', 'last': 'Drexel'}

Example: Using *args and **kwargs to set values of object#

class car: # defining car class

def __init__(self, *args): # args receives unlimited no. of arguments as an array

self.speed = args[0] # access args index like array does

self.color = args[1]

# creating objects of car class

audi = car(200, "red")

bmw = car(250, "black")

mb = car(190, "white")

print(audi.color)

print(bmw.speed)

red

250

class car: # defining car class

def __init__(

self, **kwargs

): # args receives unlimited no. of arguments as an array

self.speed = kwargs["s"] # access args index like array does

self.color = kwargs["c"]

# creating objects of car class

audi = car(s=200, c="red")

bmw = car(s=250, c="black")

mb = car(s=190, c="white")

print(audi.color)

print(bmw.speed)

red

250

Decorators#

Decorators a very powerful and useful tool in Python since it allows programmers to modify the behavior of a function or class. Decorators allow us to wrap another function in order to extend the behavior of the wrapped function, without permanently modifying it.

Example: Recall, Using Functions as Objects#

# Python program to illustrate functions

# can be treated as objects

def shout(text):

return text.upper()

print(shout('Hello'))

HELLO

yell = shout

print(yell('Hello'))

HELLO

Example: Passing a Function as an Argument#

# Python program to illustrate functions

# can be passed as arguments to other functions

def shout(text):

return text.upper()

def whisper(text):

return text.lower()

def greet(func):

# storing the function in a variable

greeting = func("""Hi, I am created by a function passed as an argument.""")

print (greeting)

greet(shout)

greet(whisper)

HI, I AM CREATED BY A FUNCTION PASSED AS AN ARGUMENT.

hi, i am created by a function passed as an argument.

Example: Returning a Function from Another Function#

# Python program to illustrate functions

# Functions can return another function

def create_adder(x):

def adder(y):

return x+y

return adder

add_15 = create_adder(15)

print(add_15(10))

25

In the above example, we have created a function inside of another function and then have returned the function created inside

The above three examples depict the important concepts that are needed to understand decorators. After going through them let us now dive deep into decorators

Syntax for Decorators#

@gfg_decorator

def hello_decorator():

print("Gfg")

'''Above code is equivalent to -

def hello_decorator():

print("Gfg")

hello_decorator = gfg_decorator(hello_decorator)'''

In the above code, gfg_decorator is a callable function, that will add some code on the top of some another callable function, hello_decorator function and return the wrapper function

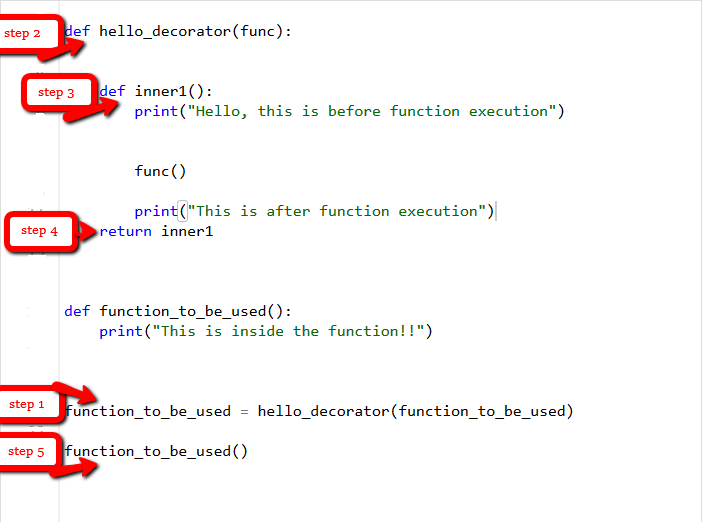

Example of How Decorators Modify Behavior#

# defining a decorator

def hello_decorator(func):

# inner1 is a Wrapper function in

# which the argument is called

# inner function can access the outer local

# functions like in this case "func"

def inner1():

print("Hello, this is before function execution")

# calling the actual function now

# inside the wrapper function.

func()

print("This is after function execution")

return inner1

# defining a function, to be called inside wrapper

def function_to_be_used():

print("This is inside the function !!")

# passing 'function_to_be_used' inside the

# decorator to control its behavior

function_to_be_used = hello_decorator(function_to_be_used)

# calling the function

function_to_be_used()

Hello, this is before function execution

This is inside the function !!

This is after function execution

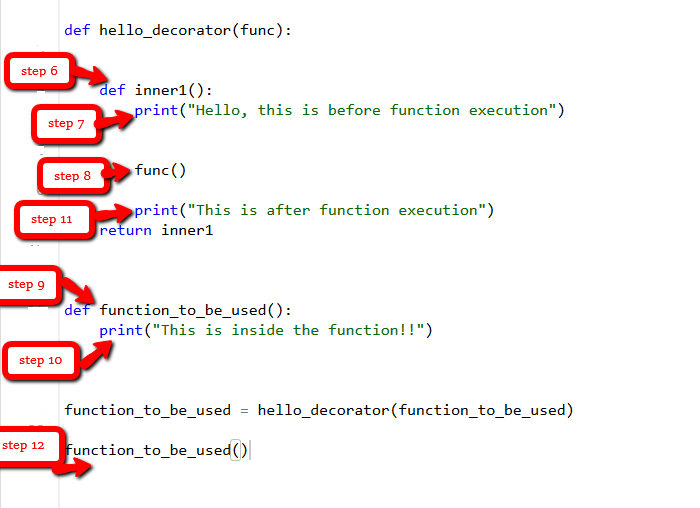

Let’s see the behavior of the above code and how it runs step by step when the “function_to_be_used” is called.

Decorator Example with Returns#

def hello_decorator(func):

def inner1(*args, **kwargs):

print("before Execution")

# getting the returned value

returned_value = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("after Execution")

# returning the value to the original frame

return returned_value

return inner1

# adding decorator to the function

@hello_decorator

def sum_two_numbers(a, b):

print("Inside the function")

return a + b

a, b = 1, 2

# getting the value through return of the function

print("Sum =", sum_two_numbers(a, b))

before Execution

Inside the function

after Execution

Sum = 3