📝 🚀 Function Scope & Variable Assignment: Lessons from the Mars Climate Orbiter#

🛰️ Engineering Context: The Mars Climate Orbiter Failure#

Fun Fact:#

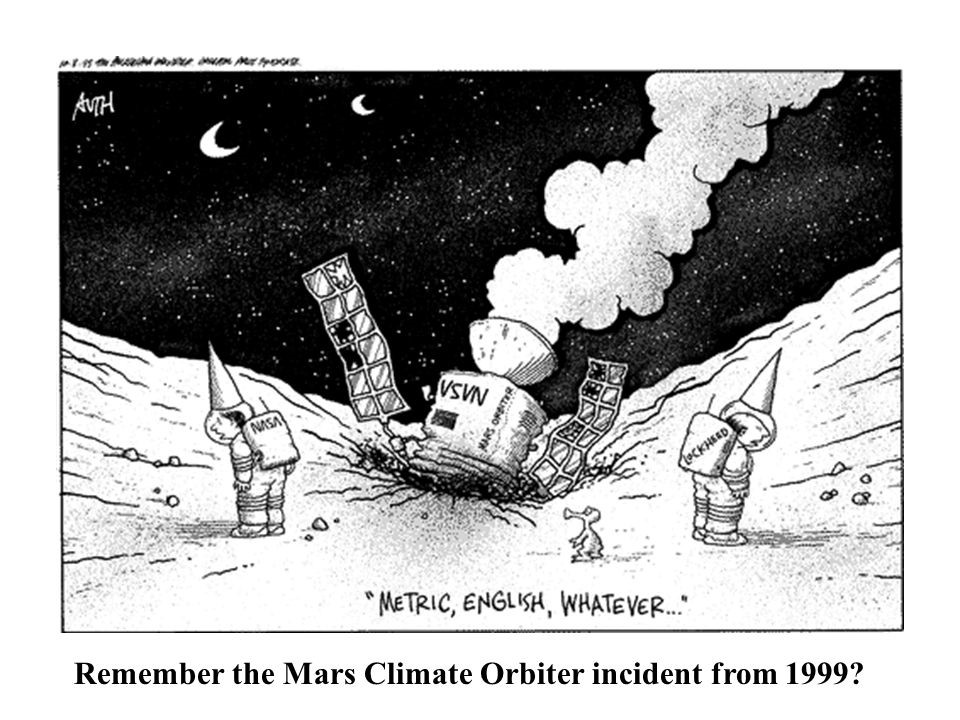

In 1999, NASA’s Mars Climate Orbiter burned up in the Martian atmosphere because one team used imperial units while another used metric units. This mistake could have been avoided with clear variable scope and proper data management!

Just like spacecraft require precise navigation, variables in Python must be correctly scoped to prevent unintended behavior!

🔄 Understanding Variable Scope#

In Python, variables have different levels of scope, affecting where they can be accessed:

Local Scope: Defined inside a function, accessible only within that function.

Global Scope: Defined outside functions, accessible throughout the program.

Enclosing Scope (Nonlocal): Applies to nested functions.

Built-in Scope: Refers to Python’s predefined names.

🏗️ Example 1: Local Scope (Variables Inside a Function)#

Local variables exist only inside the function where they are defined.

def convert_to_metric(miles: float) -> float:

"""Converts miles to kilometers."""

conversion_factor = 1.60934 # Local variable

return miles * conversion_factor

# Example Usage:

distance_km = convert_to_metric(100)

print(distance_km) # Works fine!

print(conversion_factor) # ERROR: conversion_factor is not defined outside the function

Best Practice:#

Use local variables whenever possible to avoid unintended modifications to global values.

🌍 Example 2: Global Scope (Variables Outside Functions)#

Global variables can be accessed inside functions, but modifying them requires explicit declaration.

unit_system = "imperial" # Global variable

def check_units():

"""Uses a global variable inside a function."""

print(f"The current unit system is: {unit_system}")

# Example Usage:

check_units() # Works fine!

The current unit system is: imperial

Modifying Global Variables (⚠️ Use with Caution)#

unit_system = "imperial"

def switch_to_metric():

global unit_system # Required to modify a global variable

unit_system = "metric"

switch_to_metric()

print(unit_system) # Now 'metric'

metric

Best Practice:#

Minimize global variables to prevent accidental modifications in complex programs.

If modification is necessary, use

globalsparingly.

🔄 Example 3: Enclosing (Nonlocal) Scope in Nested Functions#

When a function is inside another function, it can access enclosing variables using nonlocal.

def mission_control():

"""Nested function example: Adjusts thrust factor."""

thrust_factor = 0.85 # Enclosing variable

def adjust_thrust():

nonlocal thrust_factor

thrust_factor += 0.05 # Modifies enclosing variable

adjust_thrust()

return thrust_factor

# Example Usage:

print(mission_control()) # Outputs 0.90

0.9

Best Practice:#

Use

nonlocalonly when necessary—prefer returning values instead.

🔥 Example 4: Built-in Scope (Reserved Keywords & Functions)#

Python has predefined functions and keywords available globally.

print(len([1, 2, 3])) # Uses built-in len()

3

Avoid overwriting built-in names:

len = 100 # Bad Practice!

print(len([1, 2, 3])) # ERROR: len is now an integer

Best Practice:#

Do not redefine built-in functions or keywords like

max,len,sum.

🎯 Key Takeaways#

✅ Use local scope whenever possible to prevent conflicts.

✅ Minimize global variables to reduce unintended side effects.

✅ Use nonlocal for modifying nested function variables, but prefer returning values.

✅ Avoid overriding built-in functions to prevent unexpected behavior.

🎯 Just like NASA learned from the Mars Climate Orbiter failure, proper scoping ensures program stability and accuracy!